Samuel Yellin and the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Sketches in iron by Philadelphia's master metalworker

Learn more about Yellin's unique sketch in iron for an unrealized commission.

12/02/2021 News and Film, 20th Century and Contemporary Design

To call Samuel Yellin (1884-1940) one of the most important metalworkers of his era is almost an understatement. Though Yellin referred to himself as a master blacksmith, he occupies a greater role in the history of architecture and the decorative arts than this functional title suggests. Yellin was of course highly technically skilled, but he was an artist and designer as well – a tastemaker who influenced fine residential, commercial, and interior design throughout the first half of the twentieth century.

Lot 42 | Samuel Yellin, "Sketch in Iron," A Study for the Central Savings Bank, New York City, circa 1926-1928 | $6,000-8,000

Freeman’s December 8 Art and Design sale features five lots of Yellin’s work, and three of these offer an uncommon point of entry into the celebrated artisan’s world. These are “sketches in iron,” produced by Yellin as representative models for major projects he was engaged with at the height of his career. It is exceedingly unusual to have a three-dimensional artifact of the creative process itself survive, and here we have two tied to important architectural projects that survive today. Lot 42 (estimate: $6,000-8,000) mirrors the figural heads atop the window grilles at the Central Savings Bank (1926-28) on New York’s Upper West Side, and Lot 43 (estimate: $4,000-6,000) anticipates the massive iron gates at the Packard Building (1923-24) in Philadelphia.

Lot 43 | Samuel Yellin, "Sketch in Iron," A Study for the Packard Building, Philadelphia, circa 1924

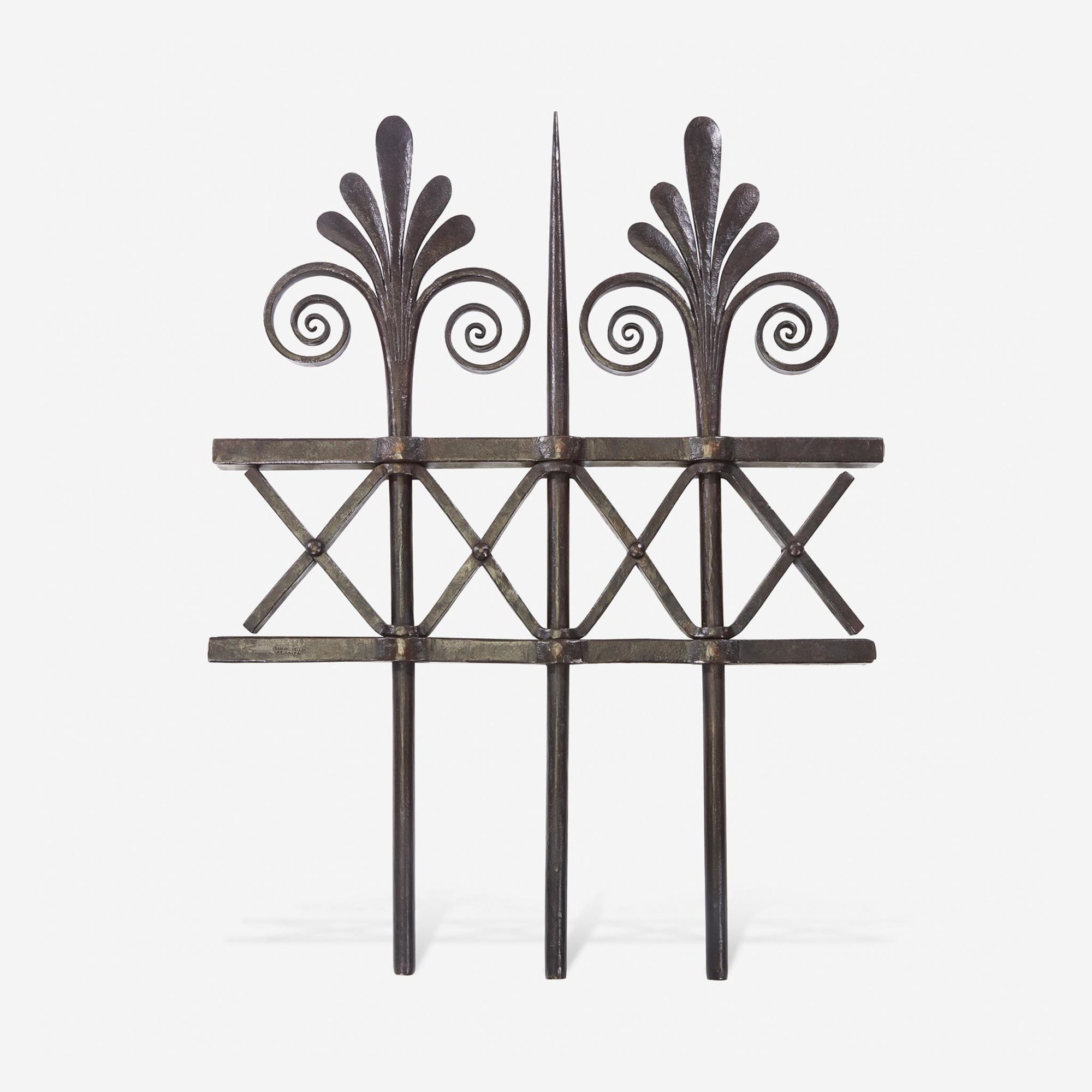

Lot 45 (estimate: $8,000-12,000) is rarer still, as this iron sketch (for an exterior window guard at the Philadelphia Museum of Art) was never commissioned. Designed in late winter 1924 for the Museum’s main building, it is a unique example of Yellin architectural ironwork that never reached a final form; it gives us a striking view only of what might have been.

Lot 45 | Samuel Yellin, "Sketch in Iron," A study for the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1924 | $8,000-12,000

Built between 1919 and 1928, the Philadelphia Museum of Art was an architectural collaboration between the firms of Horace Trumbauer and Zantzinger, Borie and Medary, and is immediately recognizable due to its polychrome terracotta exterior decoration. Knowledge of architectural paint practices in antiquity had greatly expanded in the early twentieth century, and Yellin created a design for the building’s ground floor exterior window guards that matched the exuberant archaic fantasy of the museum building itself. With spears and palmette finials that read as a primitive variation of an anthemion, the design has the basic elements of a neoclassical grille, including straight pickets and rails, accented with two rows of cross-form braces.

Yellin imbues the form with his own signature modeling: the iron sketch has a hand-worked softness to it, a characteristic missing from most architectural ironwork of the period. The finials recall Ancient Greece, with consciously hand-finished detail work that rejects the precise uniformity of mass production (this archaeological aesthetic would have made perfect sense on a building whose designers were highly conscious of changing art-historical information on classical architecture). We also can see a plasticity here in the gentle faceting of the rails, the way they bulge around the pickets. The cross braces do not terminate in the corners of their allotted space between the vertical pickets, rather they embrace the pickets at top and bottom, merging with the adjoining brace by two thick circular washers. The end result is more fluid and expressive than any other metalwork of its era.

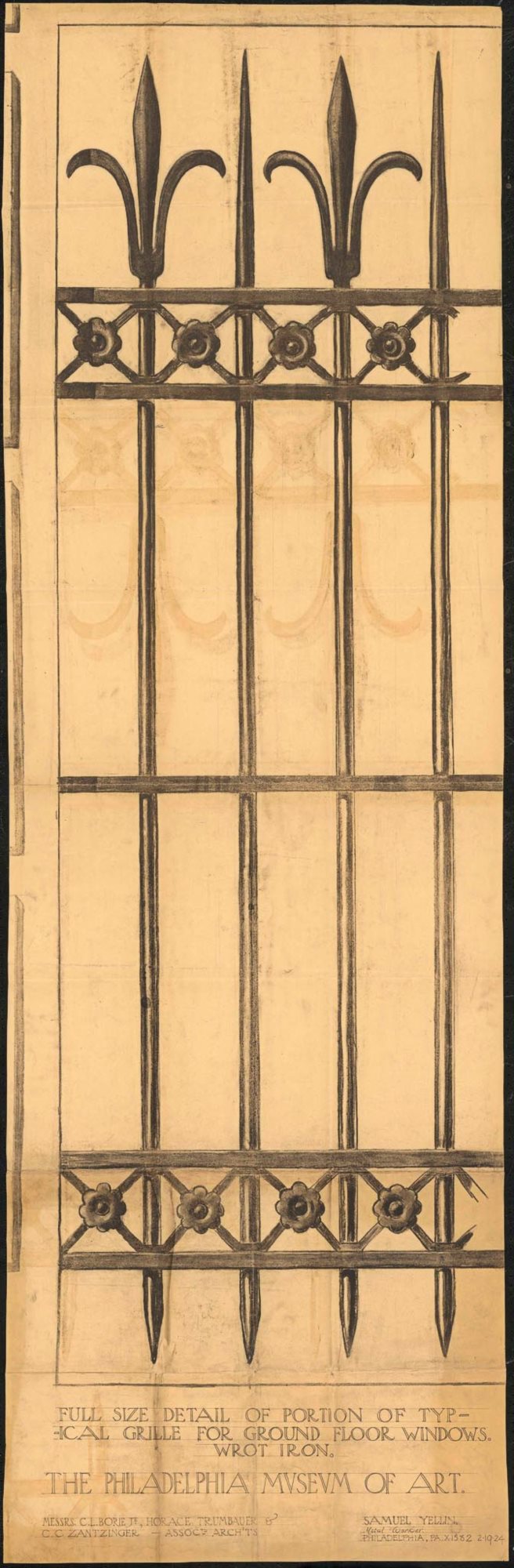

A preliminary sketch by Yellin, February 19, 1924. Courtesy of the Samuel Yellin Collections, Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

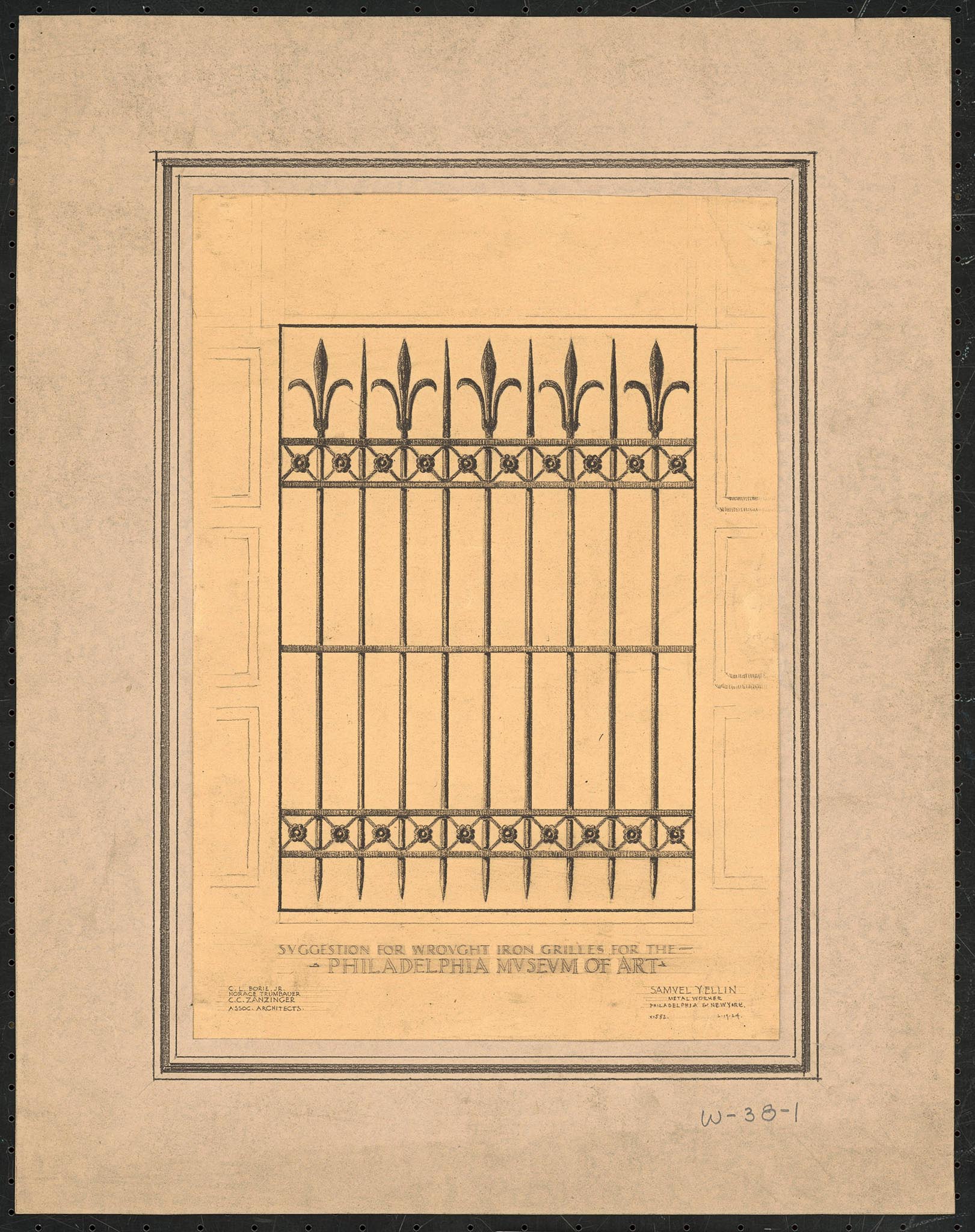

A preliminary sketch by Yellin, February 19, 1924. Courtesy of the Samuel Yellin Collections, Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

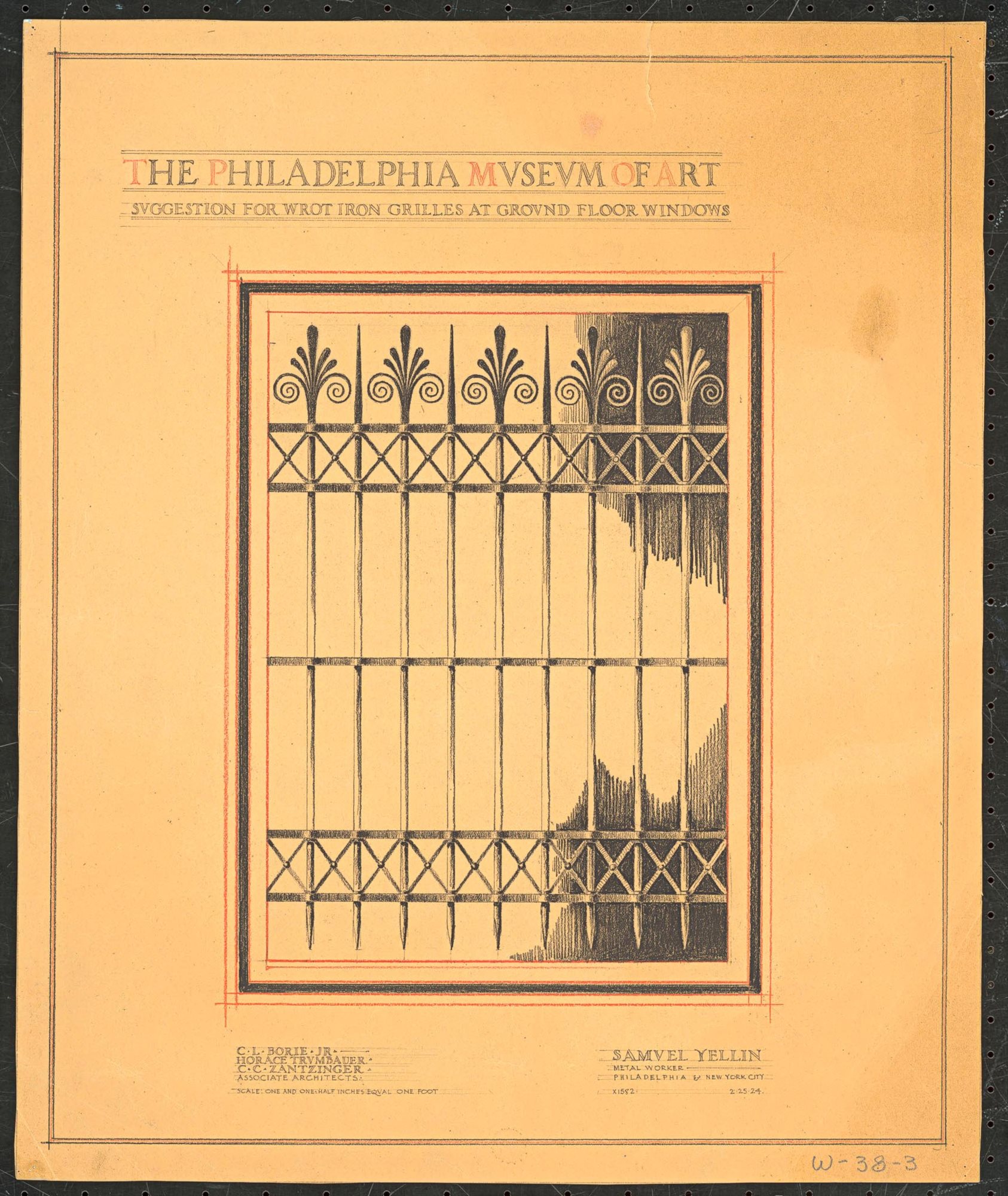

A preliminary sketch by Yellin, February 19, 1924. Courtesy of the Samuel Yellin Collections, Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

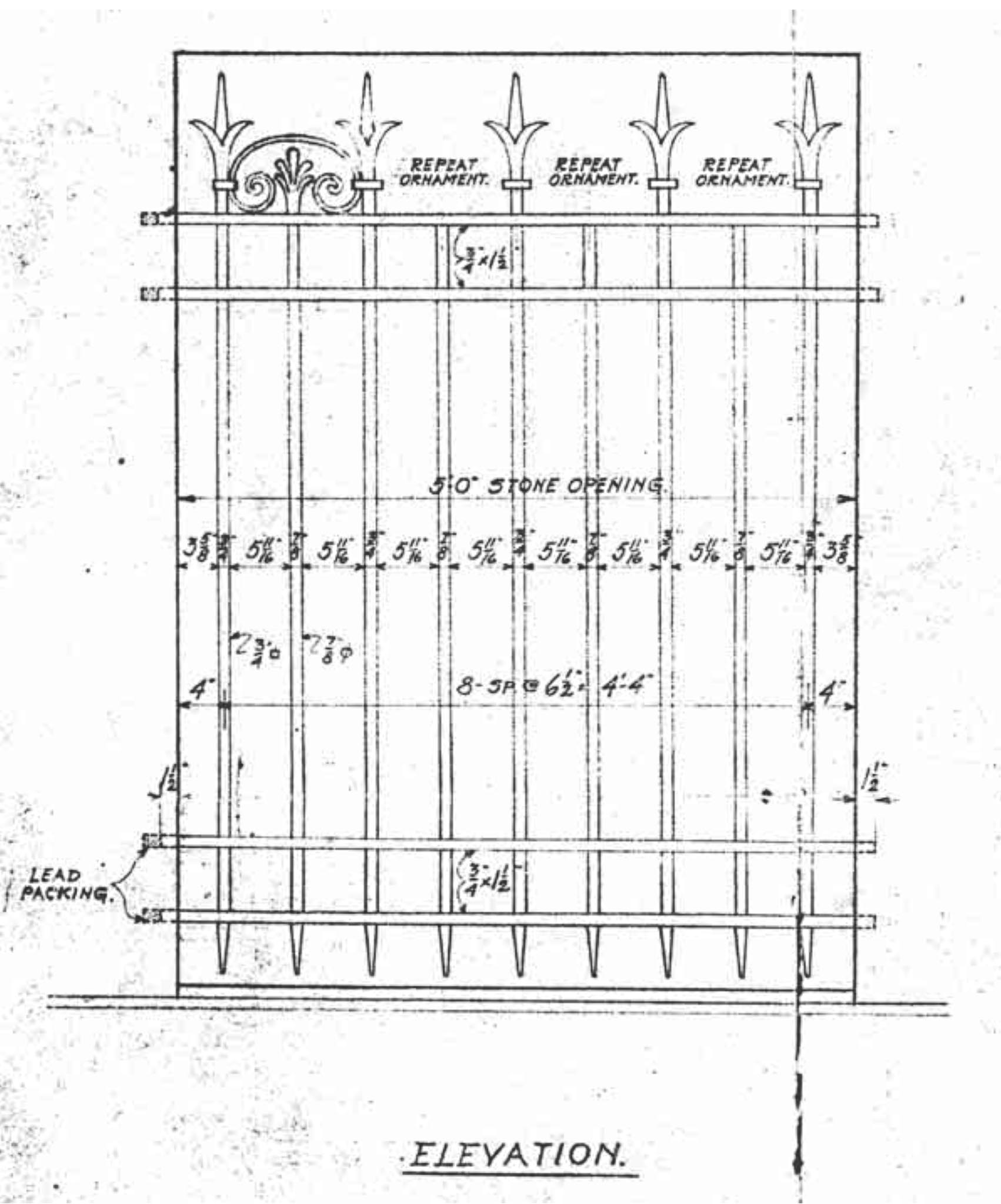

The Samuel Yellin Collection at the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania illuminates this proposed commission. Four large drawings relate to this proposal, and all bear dates within one week in February 1924. The first two are dated for Tuesday, February 19, with one being a large-format draft for a sectional view of the window guard and the other a draft presentation drawing of the entire guard. Here we see the evolution of Yellin’s design, as both these drawings from the 19th feature rosettes in the center of the cross braces, and a less expressive series of spears and three-point finials.

Yellin's working drawing for the window guard from which the present lot was fabricated, February 20, 1924. Courtesy of the Samuel Yellin Collections, Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

The next day, Wednesday the 20th, the final design comes together: a freehand working drawing on heavy stock survives (above), dated the 20th, with all the design elements present in Lot 45. This working drawing has scuffs and burn holes in it, and was almost certainly in the presence of the iron sketch while it was being produced. Lastly, we have a final presentation drawing (below) dated Monday, February 25th. This was likely presented to the Museum and/or representatives from the two architectural firms, along with the sketch in iron, for review.

The final presentation drawing for the window guard, February 25, 1924. Courtesy of the Samuel Yellin Collections, Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

It isn't clear why the Museum opted not to pursue Yellin’s design, but it was not due to lack of familiarity or positive feeling toward the master blacksmith. Yellin was close to several of the museum’s officials and donors, and would go on to consult for the institution through the late 1920s and 1930s on historic metalwork in its collections. The museum ironwork commission was eventually awarded to Tiffany Studios.

While better known for their glass works and other interior decorative items, Tiffany Studios had contained an architectural metalwork division since the late nineteenth century. It is more typical to see Tiffany metalwork in the presence of other Tiffany commissioned work (the firm’s stained-glass windows paired with their metal doors on a mausoleum, for example), but the exterior ironwork on the Philadelphia Museum of Art is a fascinating example of the firm’s metalwork standing on its own.

Tiffany Studios elevation drawing for iron window guards, September 25, 1924. Courtesy of the Archives at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Coming late in the Tiffany Studios timeline, the ironwork they produced for the museum is more restrained than Yellin’s proposed design. The ornamentation along the top rail is smaller and denser than Yellin’s, and it omits the two registers of cross-bracing, opting for a simple grille of pickets and rails. An architectural drawing from Tiffany Studios survives in the Museum’s archives (above), dated September 25, 1924, seven months after Yellin’s proposal. While still historically and stylistically important in its own right, the Tiffany Studios ironwork lacks the suppleness of the Yellin design. This leaves the iron sketch in Lot 45 not only an important physical document from the creation of a landmark building, but an arguably superior vision of what it might have been.

View the rest of our December 8 Art and Design auction.

VIEW LOTS

Have something similar? Get in touch with our 20th Century and Contemporary Design department to request a complimentary auction estimate.