February 18, 2020 12:00 EST

European Art & Old Master Paintings

32

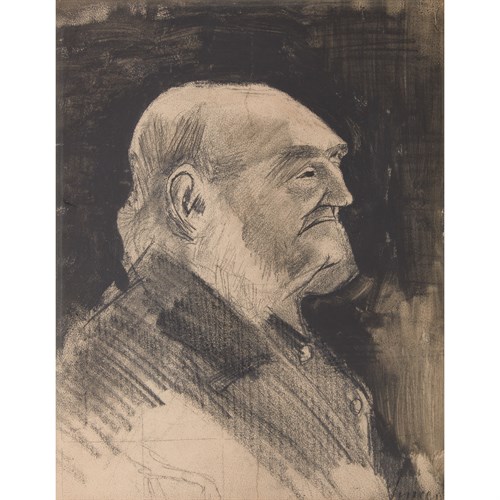

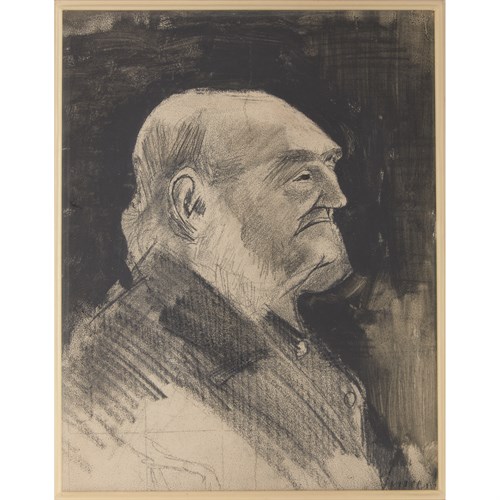

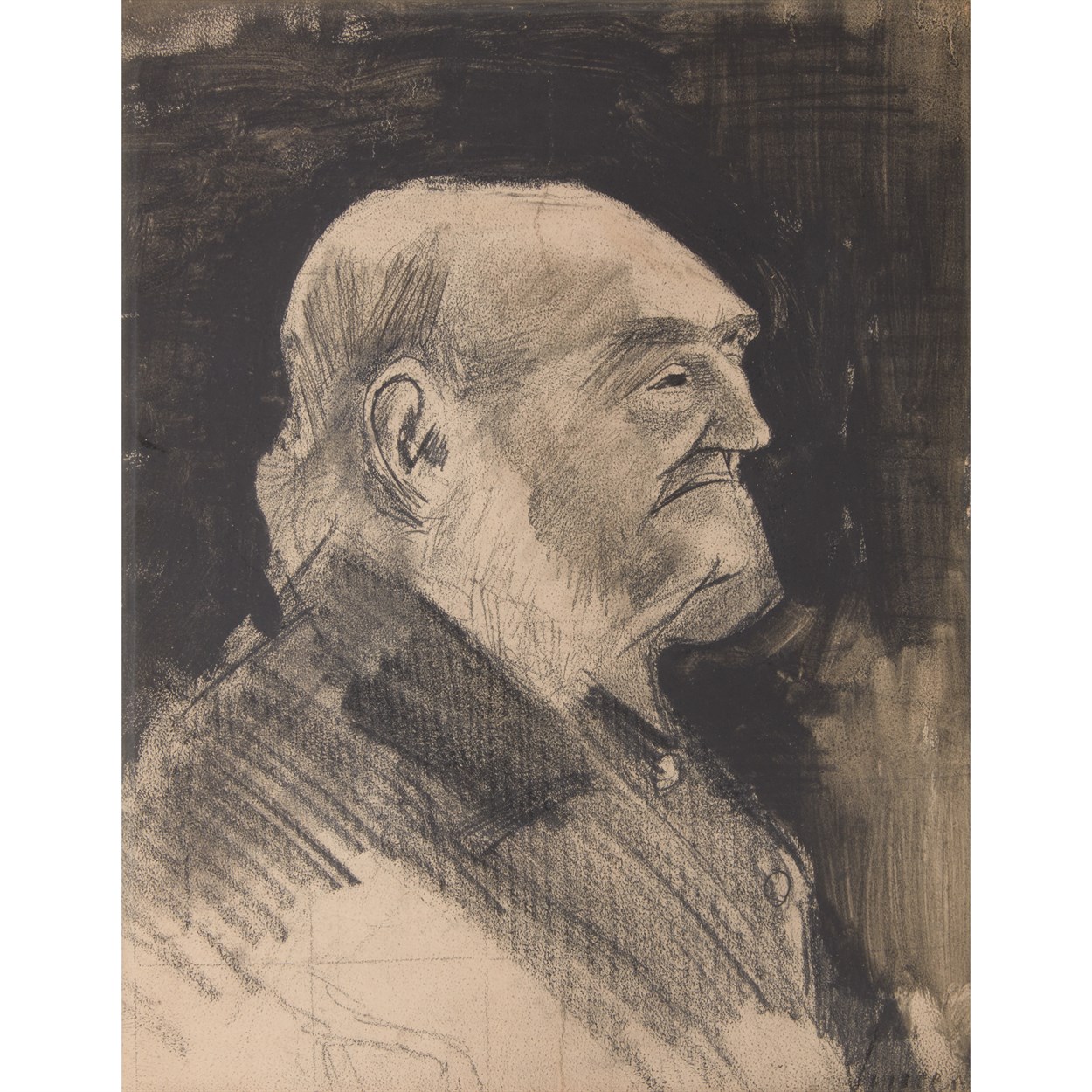

Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–1890)

Bald-Headed Orphan Man, Facing Right

Signed 'Vincent' bottom right, pencil and black wash on paper

Sheet size: 12 13/16 x 10 1/4 in. (32.5 x 26cm)

Executed in January 1883.

Provenance

Collection of Dr. H.P. Bremmer, The Hague, the Netherlands.

By descent in the family.

E. J. van Wisselingh & Co., Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Acquired directly from the above in 1968.

Private Collection, New York, New York.

Sold for $352,000

Estimated at $120,000 - $180,000

Signed 'Vincent' bottom right, pencil and black wash on paper

Sheet size: 12 13/16 x 10 1/4 in. (32.5 x 26cm)

Executed in January 1883.

Provenance

Collection of Dr. H.P. Bremmer, The Hague, the Netherlands.

By descent in the family.

E. J. van Wisselingh & Co., Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Acquired directly from the above in 1968.

Private Collection, New York, New York.

Exhibited

"Vincent van Gogh: Works from the Dutch Period," Avanti Galleries, Inc. New York, New York, October 19-December 16, 1995.

Literature

Jacob Baart de la Faille, The Works of Vincent van Gogh: His Paintings and Drawings, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1970, no. F 955, p. 356 (illustrated as Bald-Headed Orphan Man Facing Right).

Jan Hulsker, The Complete van Gogh: Paintings, Drawings, Sketches, Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1980, no. 355, p. 85 (illustrated as Orphan Man, Bareheaded, Head).

Jacob Baart de la Faille, Vincent van Gogh, The Complete Works on Paper, Catalogue Raisonné, A. Wofsy Fine Arts, San Francisco, 1992, Vol. I, no. 955, pp. 246-247 (illustrated in Vol. II, pl. XXXIII as Bald-Headed Orphan Man Facing Right).

Jan Hulsker, The New Complete van Gogh: Paintings, Drawings, Sketches, Meulenhoff, Amsterdam, 1996, no. 355, p. 85 (illustrated as Orphan Man, Bareheaded, Head).

Note

In December 1881, Vincent van Gogh left his hometown of Etten to settle in The Hague, southwest of the Netherlands. This sudden move followed a violent argument with the artist's family, who reproached his recent infatuation with his recently widowed cousin, Kee Vos, and looked down on his mediocre career, which they thought was bound to fail. Yet when he arrived in The Hague, then twenty-eight-year old van Gogh was full of hope and determined to prove his family wrong by succeeding as an independent artist. He rented a studio on the outskirts of the city and initially began collaborating with his relative Anton Mauve, one of the leading artists of the Hague School. Rather soon thereafter however, the quick-tempered artist pushed his colleague away and ended up alone in a foreign town, without many means to survive.

Undeterred, van Gogh continued to work on several projects with the same passion and optimism. He painted often in watercolor, and was encouraged by his brother to make substantial progress in oil painting. However, it was about this time that Vincent also discovered a passion for chalk and charcoal drawing, which he practiced extensively. His interest in black and white compositions was fueled by the numerous prints and illustrations he studied, and sometimes even collected, mostly from renowned British publications available in the Netherlands. Such prints were affordable and confirmed the artist's initial desire to sketch groups of popular figures, either outdoors or indoors, in the vein of Hubert von Herkomer. Herkomer's Sunday at the Chelsea Hospital, an immensely popular print depicting an old war veteran slumped over dead (and later the subject of an acclaimed painting at the Royal Academy), was an important source of inspiration for van Gogh. Obsessed with drawing figures, the artist recruited models wherever he could, accosting strangers at train stations, and even seeking out people in soup kitchens, orphanages, and hospices. As the artist explained to his brother Theo, the task was an arduous one: "I have great trouble with models; I hunt for them, and when I find them, it is hard to get them to come to the studio; often they do not come at all" (Letter to Theo van Gogh, dated January 12-16, 1882). Fortunately, the artist's luck turned in September 1882, when he started looking for new models in the Dutch Reformed Old Men-and-Women's House located in Geest, on Om Bij Street.

There, van Gogh discovered a seventy-two-year-old deaf pensioner named Adrianus Jacobus Zuyderland, who would become the artist's most frequent model, not only in the Hague, but throughout his entire career. The man was first mentioned by van Gogh in a letter to his friend Anthon van Rappart, dated September 19, 1882: "Anyway, lately I've also been painting and watercoloring, and in addition I'm drawing many figures from the model as well as sketches on the street. Lately I've quite often had a man from the Old Men's Home to pose." (quoted in Leon Jansen, Vincent van Gogh: Ever Yours, the Essential Letters, New Haven, 2014, p. 239). Zuyderland caught van Gogh's attention because of his striking features (small, heavy-lidded eyes, large ears, imposing whiskers and hooked nose) and overall attitude. His versatility and patience as a model also appealed to Vincent, who would sketch him three days a week for several hours without any complaint. The artist further dressed him up in various outfits, each associated with a different prop such as a broom, an umbrella or a cane, so as to transform him into a new character, making his sketches more interesting and lively.

The present drawing was executed in early January 1883; it is therefore one of the last representations of Zuyderland that van Gogh made in the Hague before moving to Rotterdam later that year. Here, the old man is represented as a typical orphan (or "weesman"), wearing the traditional long military-style overcoat with its distinctive gold buttons, not too dissimilar to the soldiers' uniforms shown in Herkomer's Chelsea Hospital. Contrary to previous portraits in which he is caught performing humble daily activities, such as eating soup, holding a beer or drinking coffee, Zuyderland here is shown in profile, most likely seated on a chair, and looking proudly ahead, almost defiantly. The image is miles away from the dramatic vision of despair that was Old Man with his Head in his Hands, a preparatory study for At Eternity's Gate-also depicting Zuyderland. Here the pensioner is not caught off-guard, but consciously posing for Vincent, who shows him in the simplest form: bald-headed, without his traditional top hat or cap, almost freed from his miserable status and indigent condition at which the hat hinted. In fact, the drawing reflects van Gogh's feelings towards the old man, whom he finds reassuring and somehow protecting: "This chap has the sort of lively face that one would wish for beside a cozy Christmas fire." (Letter to Theo van Gogh, dated December 22, 1882, quoted in Vincent van Gogh: The Letters at Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam).

Over the long winter months of 1882-1883, Vincent grew attached to his model, who was always compliant, docile, and certainly glad to spend a few hours each week outside of the hospice in return for a small fee. This special camaraderie is echoed by the bold, quick and broad strokes of Vincent's pencil and charcoal on the man's prominent chin, vest and coat, as well as the soft, upturned strokes on the old fellow's hair and side-whiskers. By softening the contours of the man's silhouette and accentuating the numerous shadows around him, van Gogh departs from the usual codes of classic portraiture, although his austere rendering of Zuyderland's profile reminds us of an antique imperial coin. The portrait is remarkable for its striking monochrome palette with strong contrasts of light and dark which imbue the model with a real depth of character. This is a poignant view of a dying old man who does not expect anything else from life, whose worn visage is forever marked by adversity and sorrow-a reflection of Vincent's own troubled life at the time, and of the artist's ongoing exploration of the black and white medium.

Zuyderland may indeed have filled a very special role for Vincent. Close in age to Vincent's father, it is possible that he acted as a substitute figure, though Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith instead suggest a mirror-like image of Vincent himself: "Homeless, wifeless, childless, friendless, and penniless, Zuyderland, too, was a Robinson Crusoe in the world, marooned in the passionless present" (quoted in van Gogh: The Life, New York, 2011, p. 316). Yet by making Zuyderland his regular model, van Gogh offered him an alternative to his gloomy daily life, an escape from his bleak reality. The repeated sittings also proved that Vincent enjoyed spending time with this silent companion, and maybe found solace in helping a less fortunate soul who ultimately blessed him with a new artistic perspective and a reinvigorated confidence to continue making art.