February 22, 2022 12:00 EST

European Art and Old Masters

27

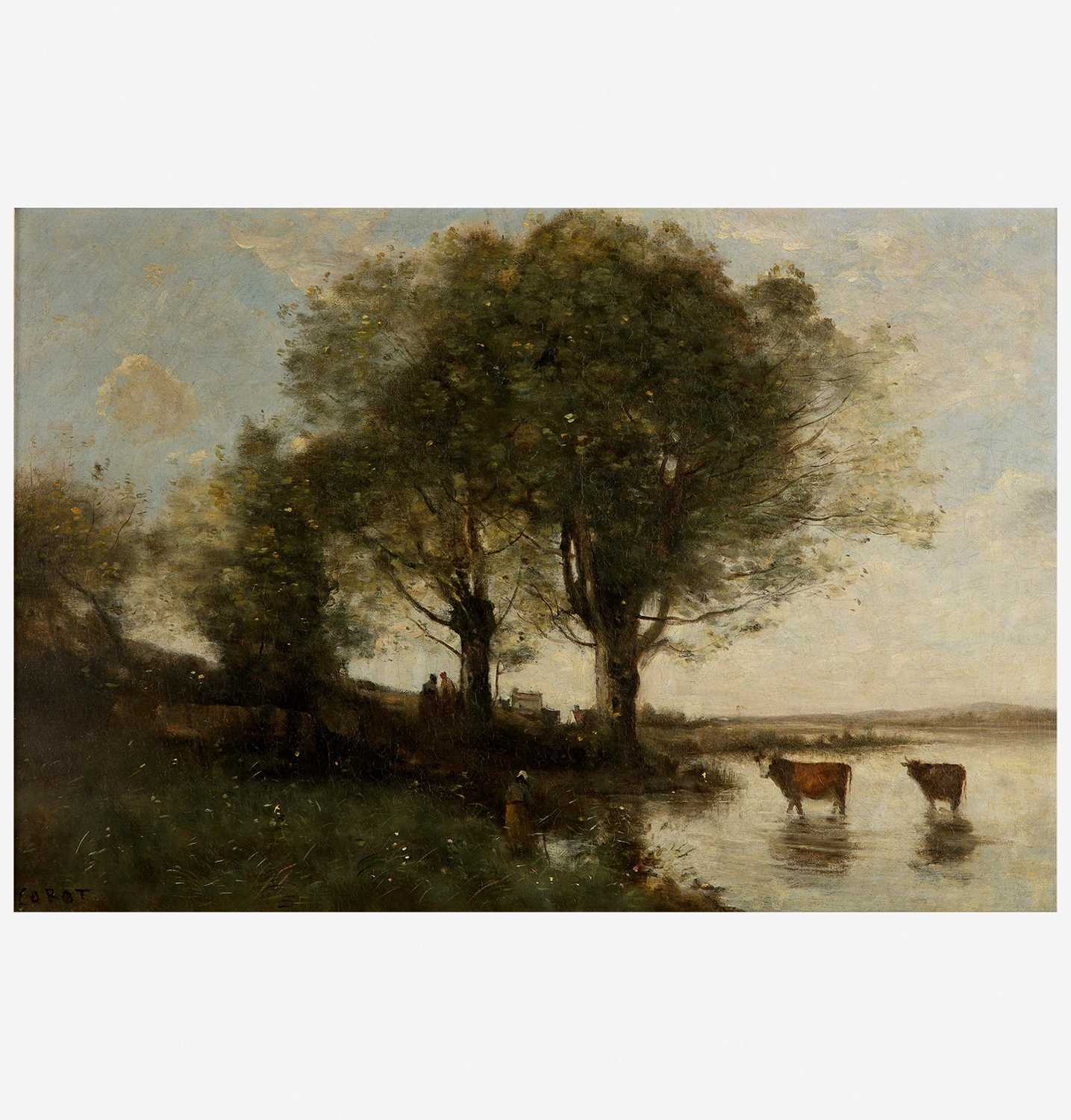

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (French, 1796–1875)

Le Rappel des Vaches

Signed 'COROT' bottom left, oil on canvas

20 x 29 1/4 in. (50.8 x 74.3cm)

Executed circa 1870.

Provenance

The Artist.

Boussod, Valadon et Cie., Paris, by 1886 (inventory no. 18016).

Acquired directly from the above on December 3, 1889.

Collection of John Parkinson, Boston, Massachusetts.

Newhouse Galleries, New York, New York.

Collection of Mrs. Adolph D. Williams, Richmond, Virginia.

A bequest from the above in 1949.

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia (accession no. 49.11.6)

Sold for $100,800

Estimated at $100,000 - $150,000

Signed 'COROT' bottom left, oil on canvas

20 x 29 1/4 in. (50.8 x 74.3cm)

Executed circa 1870.

Provenance

The Artist.

Boussod, Valadon et Cie., Paris, by 1886 (inventory no. 18016).

Acquired directly from the above on December 3, 1889.

Collection of John Parkinson, Boston, Massachusetts.

Newhouse Galleries, New York, New York.

Collection of Mrs. Adolph D. Williams, Richmond, Virginia.

A bequest from the above in 1949.

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia (accession no. 49.11.6)

Exhibited

"Corot," Wildenstein and Company, Inc., New York, New York, October 30-December 6, 1969 (loaned by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts for the benefit of the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York, Inc.).

Literature

Alfred Robaut, L’Oeuvre de Corot: Catalogue Raisonné et Illustré, H. Floury, Paris, 1905, Vol. III, p. 210, no. 1877 (illustrated).

Corot, an exhibition catalogue, Wildenstein and Company, Inc., New York, 1969, cat. no. 72 (illustrated).

Note

Le Rappel des Vaches is a wonderful example of Corot’s later style, and of his ability to capture the fleeting effects of light on the landscape. Executed in the 1870s, just a few years prior to the artist’s death in 1875, the canvas showcases all the hallmarks of his best-known, and most celebrated works. A vachère seen from behind is depicted in the process of gathering her cows, which appear to have been cooling off in the nearby river. Two distant figures, partly discernible, watch the scene from afar while a glimpse of colored roofs and white facades suggest a faraway hamlet on the break in the horizon. The scene takes place in a verdant, hilly landscape. Freshly blossomed flowers peak through the grass in the foreground while round clouds dot the bright blue sky, and announce a change in weather. The sky is shown transitioning from blue to silvery-gray (a color often associated with Corot’s work after 1850s) and the cows (one of which stares directly at us) stand out as bold masses, shadows almost, emerging from the river. Corot perfectly captures the fleeting moment of crépuscule, when the landscape is bathed in a half-light that retains much of the beauty, and of the color associated with the setting sun.

Although the work was most likely, at first, painted directly from nature, en plein air, it would be impossible to pinpoint the exact location as Corot never intended to make it too recognizable. The artist was in fact applauded for his talent of covering his tracks i.e. mixing reality with fiction, naturalism with romanticism, sometimes even adding an idealistic aesthetic to his work, so as to create a landscape composed of different influences - a trait which would earn him the nickname of “Father of Modern Landscape Painting.” The present atmospheric landscape well represents this mélange through its brushy touch, muted color palette, and overall trembling effect, which suggest a vision rather than just a view, a memory rather than an accurate representation of a locale, reminiscent of the ideals embodied by French Romantic poets Alphonse de Lamartine and Alfred de Musset. Contemporary critics often commented about this unique ability of representation: "M. Corot has a remarkable quality that has eluded most of our artists today: he knows how to invent. His point of departure is always nature, but when he arrives at the interpretation of it, he no longer copies, he remembers it.”

Le Rappel des Vaches departs from Corot’s earlier, almost architectural and oftentimes deserted landscapes. It also veers away from the traditional pastoral and classical landscapes often credited as Corot’s first inspiration. Temples have here been replaced by houses, nymphs by cowgirls and exotic animals by plain and massive farm cows. The scene is filled with a charming spontaneity that makes the painting easy to understand. It is gently animated by the several figures and animals, which evoke a simple, modest way of life. As Georges Bazin explains: “These are humble village folks, tied to the landscapes to which they are indigenous; they seem to be the rustic incarnation of those creatures and nymphs which fill Corot's "noble" paintings of this period. They travel in carts and on horseback, or simply idle by. By a pond or a river, a fisherman dreams...children keep cattle or play truant. Human toil is for Corot to be kept at arm's length, and the nature that he paints is a kind of Golden Age, where man lives, without too much effort, from the fruits of the field or the milk of his livestock." The bright hues of the golden sun (invisible on the canvas and yet perceptible through its reflecting rays in the river) blend harmoniously with Corot’s distinctive earthy tones, imbuing the whole composition with a natural warmth, a vibrancy that in a way announces Impressionism. This is not surprising, as Corot was often considered to be the bridge between Academism and Impressionism, and is known for having taught several of the soon to be famous artists such as Claude Monet, Claude Pissarro and Berthe Morisot.