February 18, 2020 12:00 EST

European Art & Old Master Paintings

37

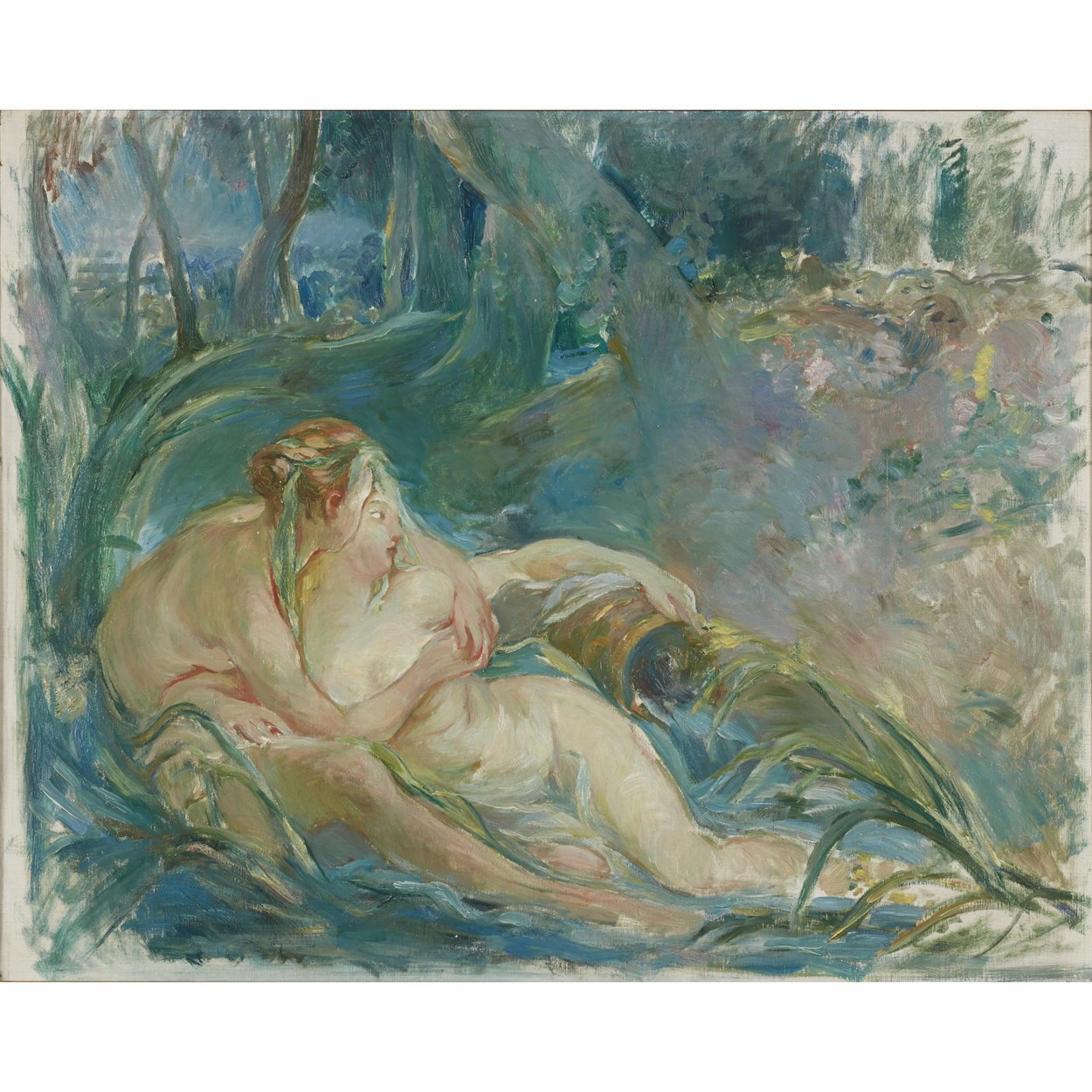

Berthe Morisot (French, 1841–1895)

Apollon Révélant sa Divinité à la Bergère Issé (after François Boucher)

Oil on canvas

25 1/8 x 31 1/4 in. (63.8 x 79.4cm)

Executed in 1892.

Provenance

The Artist.

The Artist's daughter, Julie Manet (then Madame Ernest Rouart).

By descent in the Rouart family.

Acquired directly from the above.

Private Collection, New York, New York.

Sold for $212,500

Estimated at $150,000 - $250,000

Oil on canvas

25 1/8 x 31 1/4 in. (63.8 x 79.4cm)

Executed in 1892.

Provenance

The Artist.

The Artist's daughter, Julie Manet (then Madame Ernest Rouart).

By descent in the Rouart family.

Acquired directly from the above.

Private Collection, New York, New York.

Exhibited

"Exposition Annuelle," Association pour l'Art, Antwerp, May 1893.

"Berthe Morisot," Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1896, no. 359.

"Exposition de 1907," Société du Salon d'Automne, Paris, 1907, no. 56.

"Exposition d'Oeuvres de Berthe Morisot," Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, 1929, no. 53.

"Berthe Morisot," Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris, 1943, no. 104.

Literature

Armand Fourreau, Berthe Morisot, [translated from French into English by Hubert Wellington] Dodd, Mead and Co., New York, 1925, mentioned p. 61 (not illustrated).

Monique Angoulvent, Berthe Morisot, Éditions Albert Morancé, Paris, 1933, mentioned in Chapter "Nostalgie," p. 102 and catalogued as no. 548, p. 146 (as Copie d'Apollon Visitant Latone, de Boucher).

Denis Rouart, et al., The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot with Her Family and Friends, [translated from French into English by Betty W. Hubbard] Lund, Humphries & Co., Ltd, London, 1957; and E. Weyhe, New York, 1959, mentioned p. 174 (not illustrated); also mentioned p. 197 in the subsequent 1986 and 1987 editions.

Marie-Louise Bataille and Georges Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot, Catalogue des Peintures, Pastels et Aquarelles, Les Beaux-Arts, Paris, 1961, no. 320, fig. 323, p. 45 (illustrated as Apollon Visitant Latone (Copie d'après Boucher)).

Alexandre Ananoff and Daniel Wildenstein, François Boucher, La Bibliothèque des Arts, Lausanne, 1976, fig. 1337 (illustrated).

Julie Manet, Journal (1893-1899): Sa Jeunesse Parmi les Peintres Impressionistes et les Hommes de Lettres, Librairie C. Klincksieck, Paris, 1979, mentioned p. 85.

Charles F. Stuckey and William P. Scott, "Morisot's Style and Technique," in Berthe Morisot, Impressionist, an exhibition catalogue, Hudson Hills Press, New York, 1987, fig. 111, p. 212 (illustrated as Alain Clairet, Dephine Montaland, and Yves Rouart, Berthe Morisot 1841-1895, Catalogue Raisonné de l'Oeuvre Peint, CÉRA-nrs editions,

Montolivet, 1997, mentioned p. 70, commented as no. 324, illustrated p. 272 (as Apollon Visitant Latone).

Ann Dumas et al., "Painted in an Hour: Impressionism and Eighteenth-Century French Art," in Inspiring Impressionism: The Impressionists and the Art of the Past, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2007, mentioned p. 139 (not illustrated).

William P. Scott, "A Painter's Painter," in Berthe Morisot, Woman Impressionist, an exhibition catalogue, Rizzoli Electa, New York, 2018, fig. 4, p. 162 (illustrated as Apollo Revealing His Divnity Before the Shepherdess Issé).

Marianne Mathieu, "Une Artiste en Devenir," in Berthe Morisot, an exhibition catalogue, Coédition Musées d'Orsay et de l'Orangerie, Flammarion, Paris, 2018, fig. 105, p. 189 (illustrated asApollon Visitant Latone, d'après Apollon Révélant sa Divinité à Issé).

Note

By embracing an artistic career at an early age, Berthe Morisot purposely went against the etiquette of the time, which encouraged women of the bourgeoisie to paint only as a pastime. Yet, Morisot's sheer passion and doggedness eventually allowed her to become one of the most daring painters of her time. Alongside her contemporaries Claude Monet and Edgar Degas, she was a major figure of Impressionism, and a true modernist who masterfully blurred the boundaries between sketches and finished works and pushed the limits of portraiture, landscape and genre painting altogether.

Considered the supreme painter of modern femininity for choosing elegant Parisian women as her subjects, along with her bright palette and showy brushwork, Berthe Morisot also channeled aspects of the Grande Tradition of French painting. In 1890-1891, the year before she completed the present painting, the artist confessed in her diary, "I like either extreme novelty or things of the past." (quoted in Berthe Morisot, an exhibition catalogue, Vevey, 1961, p. 53). Similar to every other artist of her generation, Morisot started copying Old Masters at the Louvre. But unlike her male peers, she continued to revere the art of the past as she matured (frequently visiting museums to copy paintings from the Renaissance onwards) and even incorporated elements of past iconographies into her own art. Specifically, Morisot held a deep affection for 18th century Rococo art. Long thought to be a distant relative of Jean-Honoré Fragonard, her work was hailed as a continuation of his lush, sensuous paintings of beautiful women, in harmony too with Jean-Antoine Watteau's intimate, pretty-in-pink atmospheres. Like her good friend Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Morisot was particularly sympathetic to the œuvre of François Boucher, whom she revered and promoted from the 1880s onward.

Morisot copied two works by François Boucher during the last decade of her foreshortened life. First, she reworked a section of Vénus Demandant à Vulcain des Armes pour Énée (1732) during a visit at the Louvre in 1883-1884. She proceeded to hang this piece above a large Louis XIV mirror in the white drawing room of her new home at 40, rue de Villejust in Paris, where she greeted numerous guests. The present work is the second copy she made. It was executed in the fall of 1892, while the artist was visiting the Musée des Beaux Arts de Tours with her daughter, Julie. It is a direct variation of the bottom left quadrant of Boucher's 1750 Apollon Révélant sa Divinité à la Bergère Issé. As in her previous copy of Boucher's painting, Morisot here focuses her attention on a small section of the painting: a pair of voluptuous nymphs swiftly caught in a delicate embrace near a forest stream. Apart from the theme, which is so distinctly Rococo, the painting also revives the 18th century technique known as pochade, a sketch which quickly captures the colors and atmosphere of a scene. Through her fragmented touch, Morisot essentially dissolves the contours of the composition into one jubilant, chromatic playground, thus giving the impression that the painting is being completed before our own eyes. The artist here shows a great facility for interpretation, dextrously rendering the delicate blues and pink, nacreous flesh tones of Louis XV's famous painter. True to both 18th century principles and Impressionist philosophy, the creative process becomes as important, if not more so, than the finished work itself. Many critics noticed and commented on this characteristic in Morisot's œuvre. According to Nicole Myers, it is because "they didn't have a way to explain her unbelievable originality and daring, [that] they used the framework of Rococo to give words and structure for how to approach the art of a woman." (quoted in Carol Strickland, "Impressionist Berthe Morisot Finally Gets her Day," in The Clyde Fitch Report, November 18, 2018).

While the painting demonstrates an understanding of Boucher's art and palette, it also reveals a certain boldness in Morisot's artistic tastes and references. 18th century art had fallen out of fashion in the early years of the 19th century, and was slowly rehabilitated in the 1850s by Emperor Napoléon III and Empress Eugénie (who held a particular fascination for Queen Marie-Antoinette and her taste in fashion and furnishings), and by the Louvre's important inaugurations of new rooms devoted to 18th century masters such as Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin, Pierre Paul Prud'hon and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. In Morisot's time, Rococo was only appreciated by a smattering of notable figures in the art and literary scene, including Charles Baudelaire, the Goncourt brothers and Théophile Gautier. They saw in 18th century French painting the expression of the first true French style since the gothic, and celebrated its members for successfully depicting daily life in a realistic manner. For years, Morisot's interest in 18th century French art was examined through her longstanding friendship with Renoir, who was himself quite vocal about his love of Rococo, and whose studio Morisot visited for the first time in January 1886. Back then, Renoir showed Morisot his numerous preparatory studies for Les Grandes Baigneuses, a monumental composition directly inspired by François Boucher's 1742 Diane Sortant du Bain, which Renoir had seen numerous times at the Louvre since its bequest in 1852. However Morisot had already proved her allegiance to the art of the past through her early exploration of pastel tonalities, vigorous brushwork and sensual themes such as women bathing, à leur toilette or preparing for the ball-themes all born in the 18th century and re-interpreted in Morisot's time through the study of many circulating prints and lithographs.

In 1896, a memorial exhibition of Morisot's work was organized and installed by Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Stéphane Mallarmé and Renoir exactly one year after their friend's unexpected passing at the age of fifty-four. Comprised of nearly four-hundred works, among which one could find the artist's famous figural works, landscapes, marine paintings, still lifes, as well as sketches, pastels and watercolors, the show also included the two copies that Berthe Morisot modeled after François Boucher. Monet himself insisted on including them in the exhibition at the last minute; not only because of the connection to Boucher, but mostly because of how Morisot had captured the scenes through quick brushwork and energetic dabs of paint, and had mixed pastel within her oil to obtain soft, powdered colors. This radically modern technique significantly influenced Monet when he embarked on his Nymphéas series some ten years later. Reflecting upon the 1896 exhibition, art critic Paul Girard concluded while looking at Morisot's work: "It is the 18th century modernized." (Paul Girard, "Chronique du Jour" in Le Charivari, March 13, 1896 quoted in Sylvie Patry and Hugues Wilhelm, Berthe Morisot 1841-1895, Paris, 2002, p. 85).