April 29, 2018 14:00 EST

The Collection of Dorrance "Dodo" H. Hamilton

7

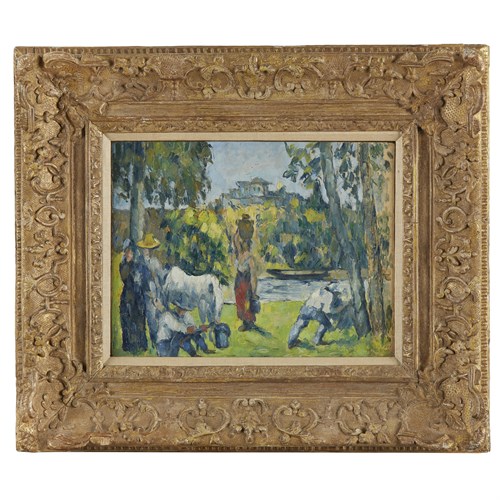

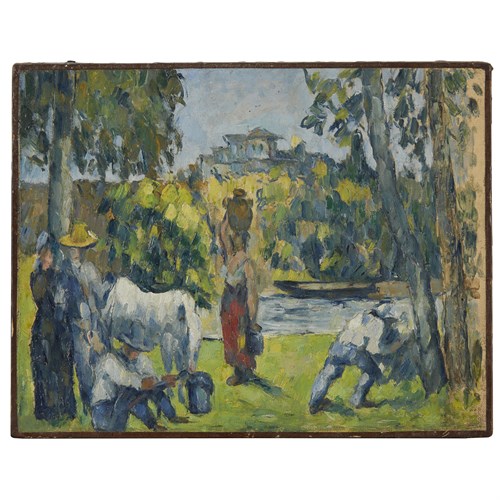

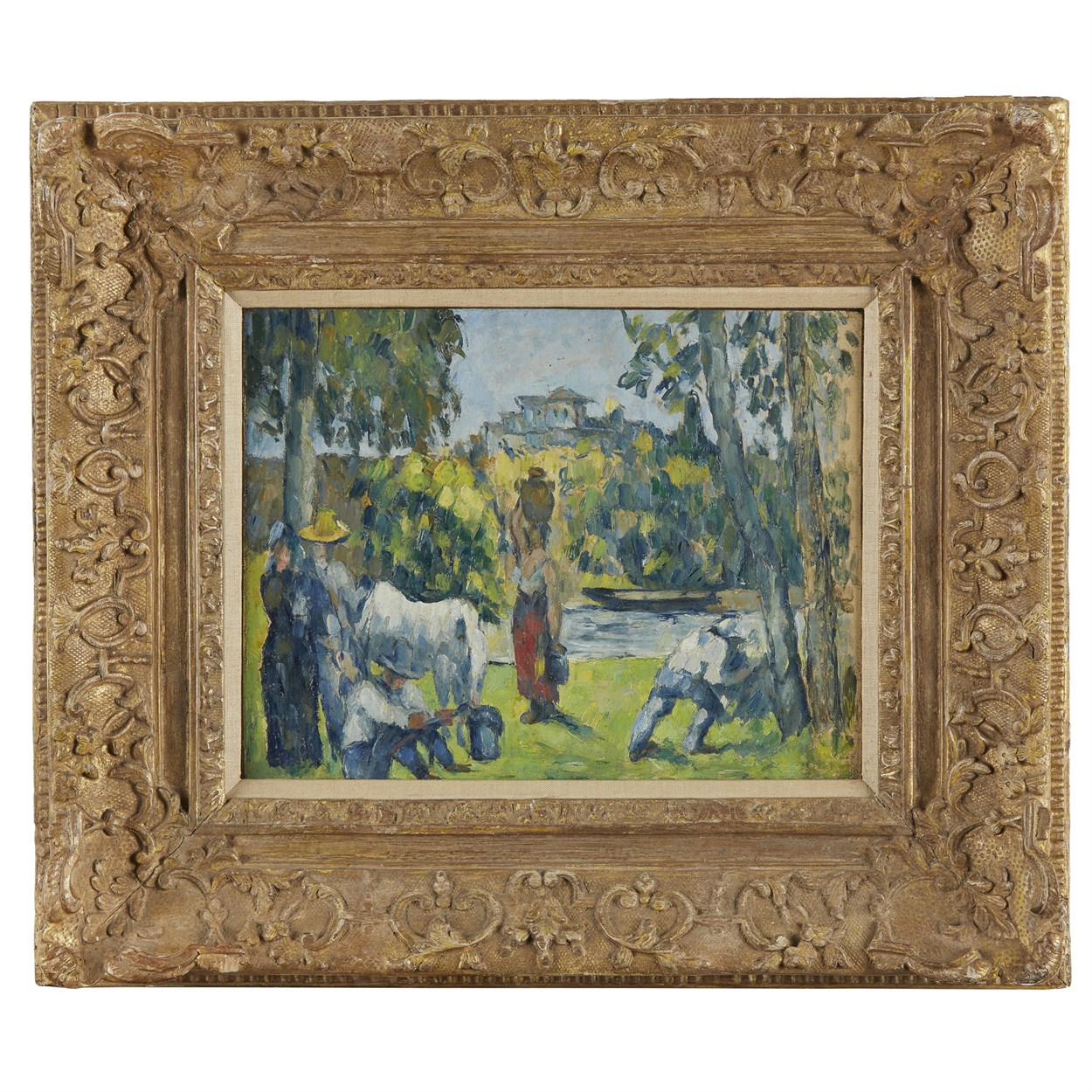

Paul Cézanne (French 1839-1906)

La Vie des Champs

Oil on canvas

Executed in 1876-1877.

10 7/8 x 13 7/8 in. (27.6 x 35.2cm)

Provenance

Collection of Ambroise Vollard, Paris, France.

Collection of Prince Antoine Bibesco, Paris, France.

Hôtel Drouot, Paris, sale of June 27, 1931, lot 75.

Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, New York.

Parke-Bernet, New York, sale of January 6, 1949, lot 48.

Galerie de l'Élysée, with Alex Maguy, Paris, France.

Acquavella Galleries, New York, New York.

Collection of Mrs. Elinor Dorrance Ingersoll.

By descent in the family.

Collection of Dorrance H. Hamilton.

Sold for $1,450,000

Estimated at $1,200,000 - $1,800,000

Oil on canvas

Executed in 1876-1877.

Provenance

Collection of Ambroise Vollard, Paris, France.

Collection of Prince Antoine Bibesco, Paris, France.

Hôtel Drouot, Paris, sale of June 27, 1931, lot 75.

Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, New York.

Parke-Bernet, New York, sale of January 6, 1949, lot 48.

Galerie de l'Élysée, with Alex Maguy, Paris, France.

Acquavella Galleries, New York, New York.

Collection of Mrs. Elinor Dorrance Ingersoll.

By descent in the family.

Collection of Dorrance H. Hamilton.

Exhibited

"Pictures, Drawings, and Sculptures of the French School of the Last 100 Years," Burlington Fine Arts Club, London, United Kingdom, 1922, no. 17 (exhibited as "Landscape").

"Paintings and Drawings by Paul Cézanne 1839-1906," Leicester Galleries, London, United Kingdom, June-July 1925, no. 18 (exhibited as "Paysage").

"Cézanne," Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, November 3-December 10, 1934, no. 7 (dated circa 1880).

"Cézanne," Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, France; Tate Gallery, London, United Kingdom and Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, May 30-September 1, 1996 (travelling exhibition, only exhibited in Philadelphia).

Literature

Ambroise Vollard, A Stockbook, no. 3314.

Walter Sickert, "French Art of the Nineteenth Century," The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 40, no. 231, p. 260-258, plate III, C.

Lionello Venturi, Cézanne: Son Art, Son Oeuvre, Pierre Rosenberg, Paris, 1936, vol. 2, no. 251 (illustrated).

Françoise Cachin, Isabelle Cahn and Walter Feilchenfeldt, Cézanne, an Exhibition Catalogue, Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1996, no. 43, p. 162-164 (illustrated).

John Rewald, The Paintings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalogue Raisonné, Thames & Hudson, London, 1997, vol. 2, no. 282 (illustrated).

Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, Cézanne and Provence, The Painter in His Culture, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2003, p. 204, fig. 5.18 (illustrated).

Denis Coutagne, "The Jas de Bouffan Landscapes," Jas de Bouffan: Cézanne, Société Paul Cézanne, Hexagone, Aix-en-Provence, 2004, p. 98-139, fig. 86 (illustrated).

Pavel Machotka, Cézanne: La Sensation à l'Oeuvre, The Eye and the Mind, Crès Editions, Marseille, 2008, vol. 1, fig. 78 and vol. 2, p. 73.

Jean Colrat, Cézanne: Joindre les Mains Errantes de la Nature, Ph.D. Dissertation, Université d'Aix-Marseille, Presses de l'Université Paris-Sorbonne, Paris, 2013, p. 232, plate 110 (illustrated).

W. Feilchenfeldt, J. Warman & D. Nash, The Paintings of Paul Cézanne, an online Catalogue Raisonné, no. 641 (illustrated).

Note

Reflecting on Paul Cézanne's career, Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) realized that few artists had a greater impact on the art of the 20th century, acknowledging "He was like the father of us all." In many respects, Cézanne was the first artist to explore abstraction in Western painting and in doing so, he paved the way for a new representation of perspective and space, free from any rule or hierarchy. Treating each aspect of his compositions with the same thoroughness, Cézanne left behind an important, yet complicated legacy: "the most difficult works of art [to access] and yet the most powerful [ones]," according to Philip Conisbee ("L'Atelier des Lauves" in Cézanne en Provence, exhibition catalogue, 2006, p. 257). Still, the artist remained misunderstood and criticized for a significant part of his life. It was not until 1895, when art dealer and gallery owner Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939) gave him his first solo exhibition, that he was able to redefine and demonstrate his true achievements. This was a major turning point for Cézanne's career and ultimately allowed him to secure a legacy as a modern master.

Paul Cézanne was born in Aix-en-Provence in 1839. The eldest of three children, he grew up in a very well-to-do family, and largely lived up to his father's great expectations. In high school, he met Baptistin Baille (1841-1918) and Émile Zola (1840-1902), with whom he formed the Inséparables school group and created life-long friendships. Upon his father's request, Cézanne studied literature and law. However, he soon abandoned his legal career to study painting instead. Like Zola he ended up in Paris, the aspiration of most ambitious provincials. There, he lived comfortably thanks to the monthly allowance his father granted him. Rejected from the École des Beaux-Arts, he attended the Académie Suisse in 1862, where he studied and copied with great interest the works of contempories such as Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) and Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), and the Old Masters like Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and Diego Velásquez (1599-1660). Cézanne's first oils are marked by a romantic touch and reveal a certain appeal for allegories. Inspired by his friend Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), he later developed an Impressionist technique, attempting to capture the ever-changing beauty of light through small dashes of color while working en plein air. As a result, he participated in the first Impressionist exhibition, organized by Nadar (1820-1910), in 1874. There, he displayed three paintings which proved radically shocking due to their style and subject. He ultimately decided not to exhibit alongside his fellow Impressionists again until 1877, the year "La Vie des Champs" was executed. Saddened by the lackluster interest in his works that year, Cézanne chose to break ties with the Parisian Impressionistic scene and returned to his native Provence for a while. He left his wife Hortense and his son Paul behind, and resumed life at 'Jas de Bouffan,' his parents' estate near Aix-en-Provence. The works produced in the South during this period are very diverse and quite difficult to date. Yet they share the same attention to light and to colorful brushwork for which Cézanne was known.

"La Vie des Champs" was produced during a period when Cézanne still embraced the influence of the Impressionist movement, along with a number of his fellow artists, including his great mentor Camille Pissarro. However, in this particular work, Cézanne departs from the typical dark, more "couillard" (bulky) style of his earlier paintings, which often portrayed violent narratives (see "The Murder," painted in 1875 and now at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, United Kingdom). Instead, "La Vie des Champs" depicts a peaceful gathering of farmhands at rest in a lush field, with a stream and verdant hill in the background.

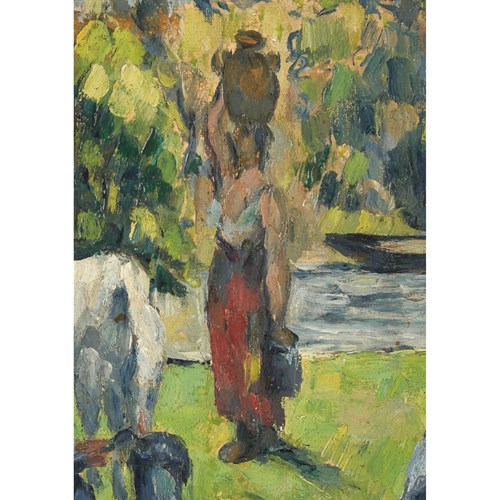

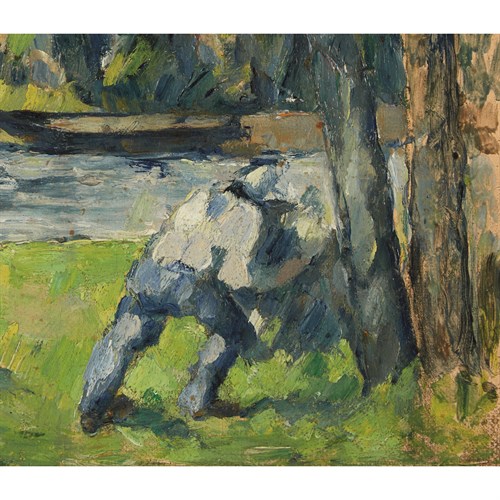

The composition seems to have been carefully planned. It is anchored by the "statuesque" silhouette of the water bearing woman in the middle; she is truly the focus of the painting. Magnified by the jug on her head, she ultimately stretches up the entire painting toward the roof in the background. The present work improves on the watercolor sketch on which it is based (and which still remains in private hands). By extending the canvas - the watercolor lacks the second tree on the right - and by depicting the landscape in greater detail, Cézanne is able to accentuate the overall symmetry of the scene. For Cézanne, "the chief thing is the picture as a whole, the coherence of the composition" Danish art critic Merete Bodelsen (1907-1986) observed (quoted in John Rewald, The Paintings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalogue Raisonné, 1997, no. 301). The great trees spreading their branches in the foreground, the small human figures below them, the long sweep of the field stretching deep into the picture and counterbalanced by the steep mountain in the background, enable the viewer to immediately embrace the painting in its entirety. The expressive brushwork also participates in the sentiment of deep harmony. They appear somewhat random, yet vivid and compact at the same time. Directionally, the touches are very distinct: horizontal in the foreground, vertical in the background as the hill fills up the entire surface of the painting.

Despite its typical Impressionist style, "La Vie des Champs" does not seem to have been directly painted sur le motif, i.e. outside. It is rather a carefully planned composition which Cézanne executed in the studio. "La Vie des Champs" actually belongs to a unique group of paintings dated to the mid-1870s. All manifest a different approach to anecdotal painting. According to Joseph J. Rishel, former curator of European Paintings and Sculptures at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, "modest in scale; they are perhaps best described as rural genre images. They have the timeless quality of visual fables." (Cézanne, exhibition catalogue, 1996, p. 162). Indeed, the different figures look like actors about to perform "in a rustic operetta" (Ibid). The entire composition itself is reminiscent of a stage set: the two trees frame the picture on both sides, as two curtains would frame a stage set. The boat, the villa and the wooded hill all appear like theater props. These elements provide a whimsical quality to the scene.

Similarly to "La Moisson," executed around the same time, and which can be analyzed as our work's compositional and stylistic twin, the landscape, specifically the house ("mas") on the top of the hill, links this setting to Provence. The farm workers are reminiscent of Camille Pissarro's, and the hilltop house in the background is typical of the South. Yet the scene is not specifically associated with any of the small villages around Aix-en-Provence. Cézanne intended the painting to be an imaginary scene, not a landscape study. As Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) immediately understood while looking at "La Moisson," "La Vie des Champs" is a vision of Provence; it suggests all its characteristic aspect on the canvas without referring to a specific place.

An admirer of Latin poetry since his youth, Cézanne conceived his native Provence to be a replica of Virgil's dreamy Arcadia, the fairytale-like country that he described in his poem "Eclogues." Much like Arcadia, Provence appeared to Cézanne as a luxuriant land with bountiful groves and meadows, alluring blue skies and a perennial summer. "La Vie des Champs" portrays this idea of a luscious and generous South. With its dazzling style and bright colors, the painting stands out as a composite of pastoral theme, bucolic landscape and realistic image of honest workers, all depicted engaged in their seasonal labor in the fields. It differs immensely from more contemporary compositions such as Van Gogh's harvest scenes in the Arles region, which incorporate factories and trains in the background. Instead, the present work is inspired from the art of the past. While many have analyzed the red dress of "La Vie des Champs'" water bearer as an homage to Camille Corot's or Eugène Delacroix's bold style, Cézanne in fact derived the motif from Nicolas Poussin's (1594-1665) masterpiece of "Eliézer et Rebecca", which shows two women with clay jugs on their heads. Both captured in an antique style, they offer a glimpse into Cézanne's true inspiration. This reference to Nicolas Poussin is not the least surprising since Cézanne always revered the Old Master, confessing he wished to "do Poussin again after nature."

"La Vie des Champs" has a long and distinguished provenance. First owned by the legendary art dealer, Ambroise Vollard, it was sold to the wealthy Romanian aristocrat, Antoine Bibesco - one of the first critics to expose the British public to works of Henri Matisse (1869-1954) and Cézanne. Following its sale at Drouot in 1931, "La Vie des Champs" departed for the United States, only to return to France once. It passed through the hands of many of the greatest galleries of the past century including the Pierre Matisse Gallery and the Galerie de l'Élysée. Dorrance H. Hamilton inherited the painting from her mother, Elinor Dorrance Ingersoll, who acquired it from Acquavella Galleries, a gallery recognized as the doorstep for important Impressionist canvases arriving in the United States. The painting was exhibited twice at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, once in 1934 and later in 1996, on the occasion of the centenary of the artist's fine solo exhibition in Paris.