February 23, 2021 12:00 EST

European Art & Old Master Paintings

56

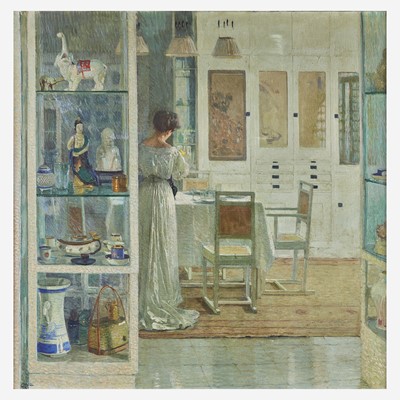

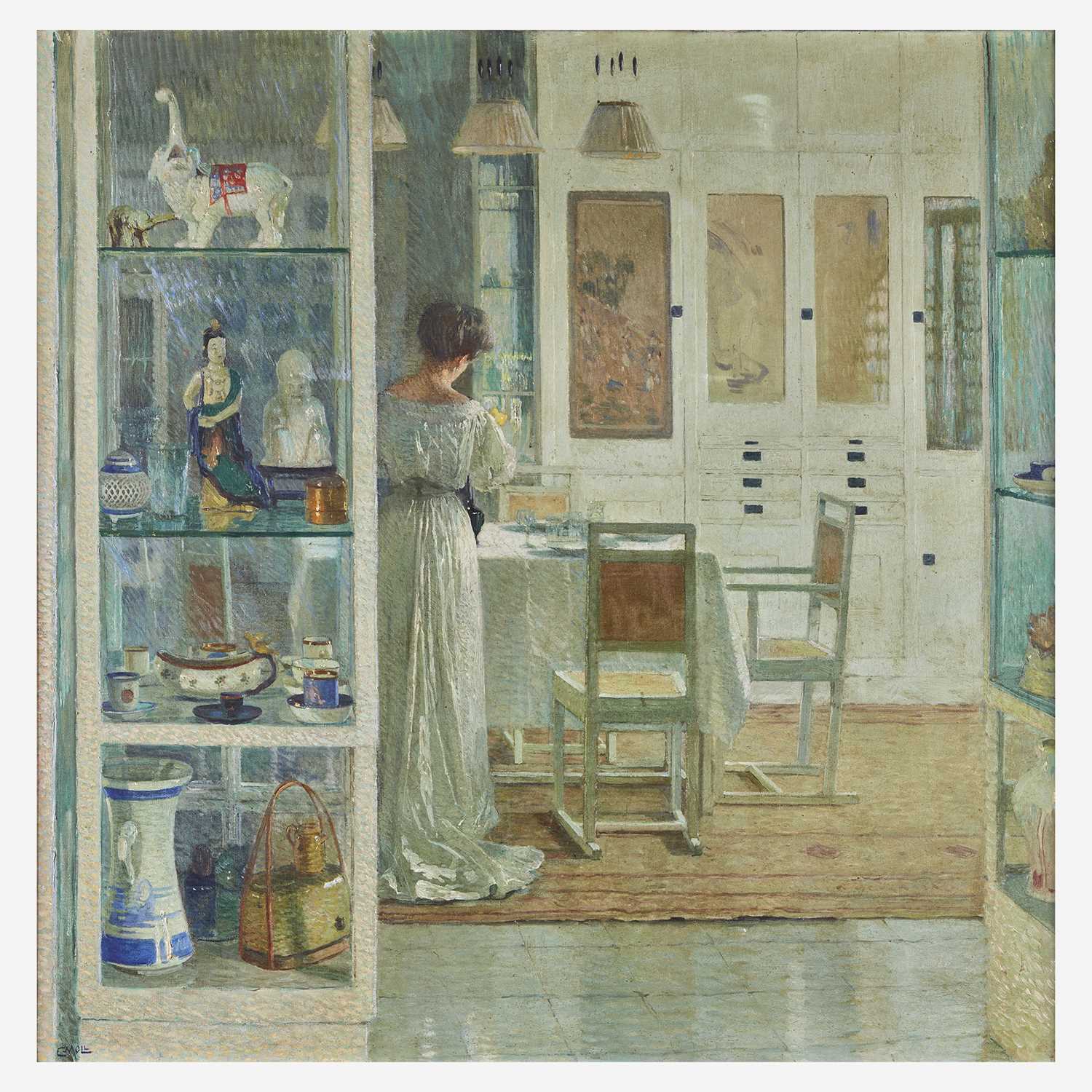

Carl Moll (Austrian, 1861–1945)

Weißes Interieur (White Interior)

Signed 'C. MOLL' bottom left, oil on canvas

39 1/4 x 39 1/4 in. (99.7 x 99.7 cm)

Executed in 1905.

Provenance

The Artist.

(Possibly) Acquired directly from the above at the "Kunstschau Wien 1908," Vienna, circa 1908.

Private Collection, Frankfurt, Germany.

By descent in the family.

Private Collection, California.

Sold for $4,756,000

Estimated at $300,000 - $500,000

Signed 'C. MOLL' bottom left, oil on canvas

39 1/4 x 39 1/4 in. (99.7 x 99.7 cm)

Executed in 1905.

Provenance

The Artist.

(Possibly) Acquired directly from the above at the "Kunstschau Wien 1908," Vienna, circa 1908.

Private Collection, Frankfurt, Germany.

By descent in the family.

Private Collection, California.

Exhibited

"Zweiten Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes," (Second Exhibition of the Association of German Artists), Ausstellungshaus am Kurfürstendamm, Berlin, Germany, May 2-October 6, 1905, no. 139.

"Ausstellung Wiener Werkstätte," (Wiener Werkstätte Exhibition), Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany, December 1906.

"Kunstschau Wien 1908," Temporäres Ausstellungsgebäude heute Wiener Konzerthaus (Temporary Exhibiton Space in front of Vienna's Concert House), Vienna, Austria, June 1-November 16, 1908, no. 6, room 11.

Literature

"Newspaper Clip," in Neue Freie Presse, No. 14632, May 19, 1905, pp. 9-10.

"Newspaper Clip," in Hagener Zeitung, No. 282, 1.12., 1906 , p. 2.

Katalog der zweiten Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes, Ausstellungshaus am Kurfürstendamm, Berlin, 1905, no. 139 (illustrated).

Katalog der Kunstschau 1908, Holzhausen, Vienna, no. 6, p. 24 (illustrated).

Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Alexander Koch, Darmstadt, Vol. XXIII, 1908, p. 45 (illustrated).

"Kunstschau Wien 1908" in Die Kunst: Monatshefte für Freie und Angewandte Kunst, 9th Year, Vol. 18, 1908, p. 532 (illustrated).

Ludwig Hevesi, Altkunst – Neukunst: Wien 1894–1908, Carl Konegen, Vienna, 1909, p. 313.

Wilhelm Schäfer, "Carl Moll," in Die Rheinlande, No. III, Vol. 21, January-December, 1911, p. 151 (illustrated).

"Ausstellungen: Wien" in Der Cicerone, Vol. III, 1911, pp. 233.

Monica Fritz, Der Wiener Maler Carl Moll (1861-1945), University Thesis, Innsbruk (unpublished), 1962, no. 202.

Hans Dichand and Astrid Gmeiner, Carl Moll: Seine Freunde · Sein Leben · Sein Werk, Galerie Welz, Salzburg, 1985, no. 53, pp. 59, 170 (illustrated).

Kirk Varnedoe, Wien 1900: Kunst, Architektur & Design, Taschen, Cologne, 1987, p. 105 (illustrated).

Cornelia Cabuk et al., Carl Moll: Monograph and Catalogue Raisonné, Ritter Verlag, Klagenfurt, Vienna, 2020, cat. no. GE 223, pp. 49-50, 51-52, 177 (illustrated p. 177).

Note

We wish to thank Ms. Cornelia Cabuk for her kind assistance in cataloguing the present work.Please note the painting is accompanied by a Certificate from the Art Loss Register, proving the work has not been registered as stolen or missing.

CARL MOLL AND THE VIENNESE SECESSION

Although he remains relatively unknown outside of his native Austria, Carl Moll was one of the leading artists in Vienna at the turn of the 20th century. In 1897, he co-founded the Viennese Secession along with Gustav Klimt, Otto Wagner and Josef Hoffmann, breaking free from the inherent conformity dictated by Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts, to promote new forms of creation. This movement in turn revitalized what was considered to be modern Austrian Art. Moll mainly painted landscapes and still lifes, all inspired by French Neo-Impressionism; but he was also known for the serene and elegant interior scenes he produced throughout his entire career, as exemplified by Weißes Interieur (White Interior), which he painted in 1905.

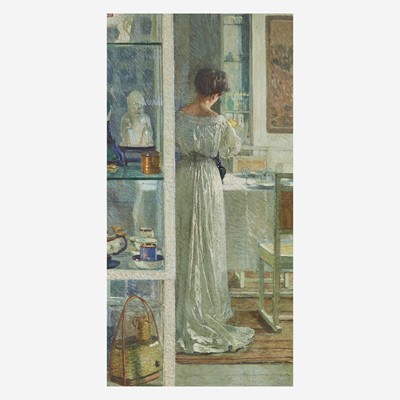

White Interior depicts a solitary female figure in the center of a highly decorated living room. Dressed in a loose, long white reform dress, the woman is shown from behind, oblivious to our presence and visibly preoccupied with arranging a bouquet of yellow tulips in an antique vase. The work is marked by a sense of domestic tranquility, and characterized by its soft, diffuse light - a trait reminiscent of 17th century Dutch painting, and especially that of Johannes Vermeer who often depicted lonely figures in enigmatic interiors, and whose oeuvre had just been rediscovered in the early years of the 20th century. The composition is carefully balanced, anchored by the sleek horizontal line of the central dining table that contrasts nicely with the two tall display cases placed on each side of the canvas in the foreground, framing the center stage. As often with Moll, the canvas is square - a format he mostly reserved for his landscapes but which he also adopted in several similar domestic scenes completed around the same time such as Frühstück (Breakfast, 1903 - Private Collection), Anna Moll am Schreibsekretär (Anna Moll at her Writing Desk, 1903 - Wien Museum) and Beim Frühstück (At Breakfast, 1903 - Wien Museum).

The square format was often used by artists of the Secession movement to achieve a harmonious effect of high artistic quality. In the present example, the form also contributes to the immediacy of the scene, inviting us to enter the space and maybe even call out the woman in front of us, in hopes she would turn around.As suggested by its title, White Interior was conceived as a pure chromatic play on the color white and its multiple nuances, which are revealed to us through Moll’s unique fragmented touch, particularly noticeable in the treatment of the light - vibrating, iridescent and pointillist. It conveys a meditative, spiritual effect to the scene, which was often the meaning attached to the color white, as used by the Symbolist artists in Vienna around 1900. As Cornelia Cabuk points out in her monograph of the artist’s work, White Interior in fact pays homage to James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s famous Symphony in White No. 1, the White Girl, which Moll had the opportunity to see when it was exhibited in Vienna in 1898, and which he used as his main reference to make his own painting more recognizable (if not desirable), especially out west. White Interior is also highly reminiscent of several portraits of women in white Gustav Klimt executed in 1904-1905, such as that of Hermine Galia, or Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein (see Lot 56 for a study of the portrait). Contrary to Klimt however, who used to represent his models facing the viewer, Moll chose to conceal the female figure from our gaze, revealing only her back, thus contributing to the overall mystery of the scene.

BERTA ZUCKERKANDL, GRANDE DAME DER WIENER MODERNE

Although her face remains hidden, the figure in White Interior is not anonymous. She is known to us as famed art critic and journalist Berta Zuckerkandl, who was considered “the puppeteer of Vienna’s cultural scene” by Karl Kraus. Married to famed anatomist Emil Zuckerkandl of the University of Medicine of Vienna, she was one of the leading Jewish figures in the city at the turn of century. She saw modern Austrian art as a way to restore Austria’s former glory and influence among the other European nations, especially Germany - which Zuckerkandl considered to be Austria’s antithesis. To that end, she entertained a long-standing relationship with many western artists, including French painter and sculptor Eugène Carrière and Auguste Rodin (whom she convinced to go to Vienna to meet Gustav Klimt). She later played a significant part in establishing a cultural and political dialogue between France and Austria during World War I, through her connection with Georges Clémenceau (whose brother, Paul, married her own sister, Sophie) and Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria known for his liberal aspirations. Zuckerkandl expressed her yearning for a new age through virulent journalism (as she wrote herself, “In this fight, my weapon was my pen (...) my battlefield the 'Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung’" - a social-democrat newspaper in which she wrote to defend avant-garde artists, especially Klimt, against controversy and censorship), as well as in her Salon.

In White Interior, Carl Moll represents Zuckerkandl in the living room of her apartment in Nusswaldgasse, the main street in Döbling, an affluent neighborhood in the heart of Vienna. There, she held a highly influential, weekly Salon (one of Europe’s last) attended by many of the leading intellectuals of the time, including writers Arthur Schnitzler, Stefan Zweig, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and Hermann Bahr, artists and designers such as Gustav Klimt, Otto Wagner, and Josef Hoffmann, and many other distinguished guests in the medical, political and musical worlds. The living room itself was decorated by Vienna’s then leading architect and designer, Josef Hoffmann, and was considered by many as the epitome of modern design. Carl Moll only represented Zuckerkandl one other time, three years later in 1908. On the second canvas, soberly entitled Interior in Döbling, Zuckerkandl is shown once again in her Hoffmann living room, but from her second apartment on the Ringstraße, above Café Landtmann. Today, the canvas still remains in private hands. Although the paintings depict the same scene, both are conceived as different exercises.Interior in Döbling can be understood as a “coloristically accentuated version” of White Interior in which Moll mainly insists on the optical illusions carried out by the reflecting light on the mirrors, the shiny oranements and the window cases (which blur out Zuckerkandl’s face). The goal, as Cornelia Cubuk explains, is to portray “the ambivalence of the visible and the exotic as an artistic phantasmagoria.”

JOSEF HOFFMANN’S INTERIOR

By representing Zuckerkandl surrounded with Josef Hoffmann’s modern furniture in both pictures, Moll aimed at showing off Zuckerkandl’s new, stylish interior to the general public. He also paid tribute to the Grande Dame of the Wiener Modern and saluted her bold support of the new generation of Viennese artists, including himself. In that sense, White Interior functions as a permanent exhibition room encapsulating the taste of the early 20th century, particularly through Josef Hoffmann’s creations. Hoffmann was revered for his modern interiors that emphasized simplified, functional forms. In 1903, Zuckerkandl characterized Hoffmann’s creations as logical, clean, and strong; aiming “for the full expression of the anatomy of the thing in its unshakable truth.” According to her, Hoffmann was “the most devoted priest” of a new, honest movement meant to improve the poor state of architecture, interior design and decorative arts that Zuckerkandl deplored when she wrote: “Vienna has lost its sense of beauty.” The apartment as shown here is a symphony of sleek, straight and pure lines and shapes. They perfectly echo Hoffman’s brand of modernism, which is traditionally defined by flattened, geometric surfaces (such as the repeated square motif throughout the composition), as well as a spare use of ornaments, and black and white color schemes. Similar to the houses he designed for the Hohe Warte art colony, where Carl Moll and his family lived, Hoffman’s furniture in White Interior displays a quest for unity of structure and harmony.

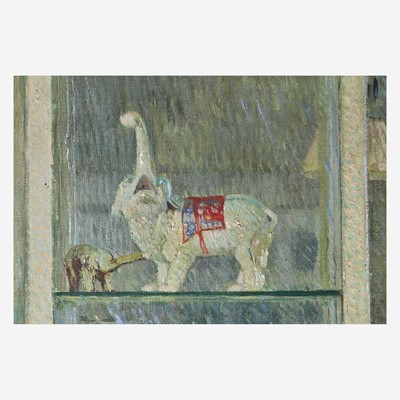

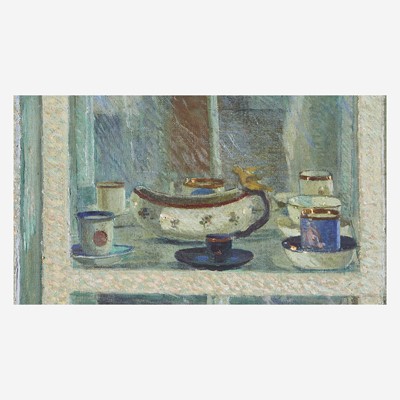

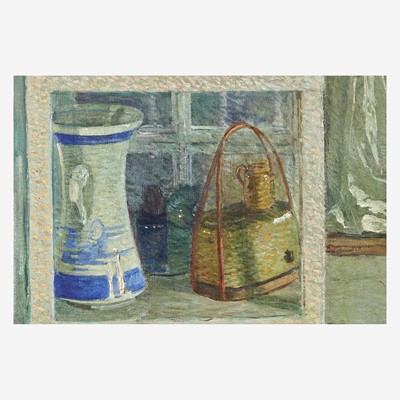

Hoffman interior also served to showcase Berta Zuckerkandl’s (and her husband’s) impressive collection of East Asian art, as seen in the pair of vitrines, where one can spot Hirado sculptures as well as porcelain tea sets and vases. Several items are listed in Emil Zuckerkandl’s 1916 Estate Sale catalogue, including the “white glazed Chinese porcelain figure of the seated Ma-Ku (Magu)” - god of a long life, and protector of women according to Chinese mythology. If Zuckerkandl’s collection of East Asian art was renowned, it was only limited in comparison to that of his brother Viktor, and his wife Paula, whom Berta both helped launch the plans for an East Asia Museum in Purkersdorf. Generally speaking, Asian Art was a vital source of inspiration in the field of decorative and fine arts in Vienna at the time. Klimt himself employed Asian motifs in his paintings and wore kimono-inspired robes in his studio. Zuckerkandl not only promoted this trend in the arts, but fully adopted it in her daily life, as revealed by the kimono she wears in Interior in Döbling, and which is loosely based on the one she is shown wearing in Dora Kallmus’s famous photograph of her in 1908. For Zuckerkandl, the kimono stood on the same level as the famed reform dress (such as the one she wears in White Interior), since its ample forms and generous lines granted a wide variety of movement to its wearer, and proclaimed its individuality. In her multiple essays, Zuckerkandl advocated this type of clothing, not only for aesthetic reasons but also for health considerations.

A TOTAL WORK OF ART

By presenting Zuckerkandl in perfect harmony with her surroundings, namely the Modern Design furniture and the Asian Art figurines, Moll shows his use and respect of foreign influences and ideas, which he assembles into one philosophy, Gesamtkunstwerk - a “total art” that mixes painting, architecture and decorative arts altogether. In the politically agitated Vienna from around 1900, the notion of interiority was at the forefront of everyone's mind, and conceived as this haven where one could safely withdraw from the public sphere. White Interior is this sacred space where Zuckerkandl leads a self-contained aesthetic totality, which revolves around the furniture, the clothing, the decorative arts and the overall architecture she chose to surround herself with, thus creating the setting for a modern, sensitive life that embodies the ideals of the Viennese Secession. As Emily D. Bilsky and Emily Braun both state in Jewish Women and their Salons: The Power of Conversation, White Interior is the ideal salon Zuckerkandl described in her writings, and through which she wanted to achieve her goals for Vienna: “As art, design, and fashion are to be integrated into a total vision of life, sociability - the salon- is part of the (...) total work of art.”

White Interior is a major work by Carl Moll, which he exhibited in Berlin in early 1905 and again at the Folkwang Museum in Essen in 1906. From that exhibition, a reviewer wrote: “that the artists have come together in their artistic sensibilities and interact organically [...] Due to the way in which Moll has pursued his whiteness through wood, porcelain, damask, and silk, through light, half-light, and shadow, the ‘Interior of Hofrat (sic) Zuckerkandl’ [...] is precisely the artistic counterpart of Hoffmann’s interior spaces.” For a long time, the canvas was thought to be lost and was only known to us through a black and white photograph taken during the 1905 exhibition. Its last public appearance was at Vienna’s celebrated Kunstschau in 1908, where it was featured alongside Gustav Klimt’s iconic Der Kuss (The Kiss), now in Belvedere Museum. It was most likely at the end of the show that Moll sold the work. Since then, the work has remained within the same private family collection, first established in Frankfurt Germany, and relocated to California, U.S.A. since 1970s.